Gold-plated teaspoons, $1000 pots of tea, truffle shavings for the owner’s dog … the economic downturn has yet to reach the dizzy heights of Vue de Monde, writes Dani Valent.

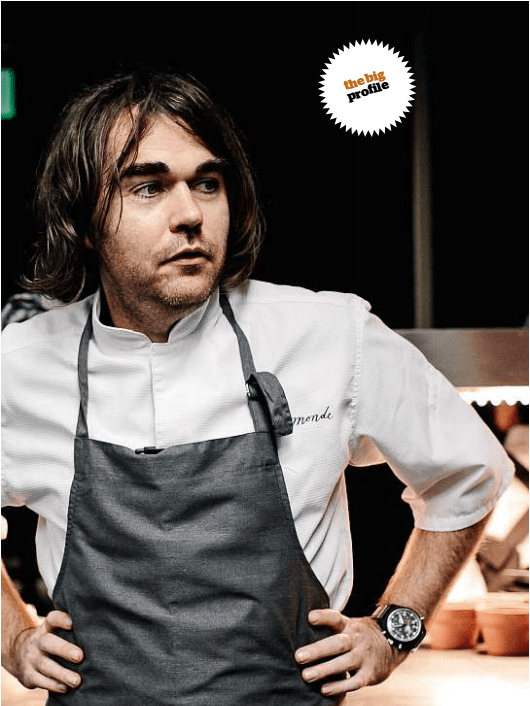

Somehow, between parking his Audi coupe in the Rialto’s underground car park and pushing the “up” button on the service lift, Shannon Bennett changes from truffle-hunting civvies into chef’s jacket and apron. He enters the Vue de Monde kitchen via a rear door, just as Saturday night’s dinner service is picking up pace. There’s a concentrated serenity to the place, creating a mood that plucks elements from operating theatre, orchestra pit and VCE exam hall. It smells of butter. Glistening marron are lined up in rows. Glass domes await hay-smoked pigeon. Tiny wafers lie in wait like offerings, attended by young chefs with palette knives. Bennett, 36, is by far the scruffiest person in his restaurant but there’s an intense and serious force field about him that’s more powerful than the levity of any rogue hair tufts. “I don’t get a buzz from walking in here,” he says. “There’s a sense of apprehension every time.” It’s a shame he doesn’t surge with joy as he begins his rounds: he might delight in the twinkling treat of the view from the 55th floor, the liveried waiters gliding about the dining floor, his crack cooking team led by head chef Cory Campbell and, especially, the diners in their big-smoke best eating trout belly with smoked eel and nasturtiums, or lamb sweetbreads, prawn and raisins and – hopefully – sinking into rapture.

Vue de Monde was recently anointed Restaurant of the Year at The Age Good Food Guide awards, one year after it moved into spectacular premises at the top of the Rialto towers. It’s the second time the restaurant has received that prize in 12 years across three venues. Last time it happened was in the 2007 Guide, one year after moving from the original Carlton digs into smart premises in Little Collins Street. That time, the award was accompanied by three hats and a score of 19/20. The following year, the restaurant lost the title, a hat, and one-and-a-half points in a fairly spectacular take-down. Bennett is understandably cautious about this year’s gong. “The award is great because it means people are enjoying what we’re doing,” he says. “But we’ve got a lot to get right before I am satisfied. We still make mistakes. I said to the team, ‘Let’s see this as a statement of where we are now. Let’s take a snapshot of it and think about where we want to be in nine months.’ If we took the other view, that we’re fantastic, we could become complacent.” Complacency isn’t a quality easily associated with Shannon Bennett. During a day spent tailing him for this story, descriptors that spring more readily to mind are energetic, driven and fiercely attentive to detail. We start at the Melbourne Art Fair, at the Exhibition Buildings in Carlton, where Bennett arrives with six-year-old daughter, Phoenix. She wears gumboots, clasps an art catalogue and happily peels off to the kids’ corral to create a clay monster. Bennett moves quickly from stand to stand, an eye out for artists he might feature in his restaurants.

“There’s a lot of crap here,” he says, stopping occasionally to snap artworks that, to his eye, transcend the morass. There’s a pitstop at the Anna Schwartz stand. The prominent gallerist met Bennett through her daughter, Zahava Elenberg, and son-in-law Callum Fraser, Vue de Monde’s architects. Schwartz introduced Bennett to the work of many in her stable, including conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth whose neon work is the artistic crux of Vue de Monde. Kosuth’s piece represents Charles Darwin’s early sketches as refracted through the ponderings of the philosopher Nietzsche. “It’s highly intellectual and very subtle as well as visual but Shannon immediately embraced the philosophies,” says Schwartz. “He approached it as he approaches everything: very vigorously and with great preparedness to understand.”

Art Fair checked off, Bennett hits the highway to Burnham Beeches, the neglected Dandenongs treasure he and property developer Adam Garrisson plan to turn into an accommodation and dining retreat. Bennett checks his phone. His wife, actor Madeleine West, is home in Melbourne with two-year-old Xascha, very pregnant, not feeling great, awaiting the birth of child number four. “This one was a surprise … a surprise we’re embracing,” says Bennett, still apparently a little gobsmacked. (Baby Xanthe is born the following week.) Phoenix dozes in the back seat alongside the magazine’s photographer and Bennett’s Australian Shepherd puppy, MJ, a truffle dog on L-plates who vomits quietly on the photographer’s lap just before we arrive.

A truffiere, a specially prepared and inoculated oak grove, has been planted at Burnham Beeches. The eventual plan is that house guests may borrow a dog, find a truffle, then cook it in their villa or have a chef cook it for them. To encourage MJ’s taste for the coveted fungus, Bennett grates a little over the dog’s dinner a couple of times a week. For today’s practice run, he wraps a truffle in cloth and buries it in the soil, marking the spot with a toothbrush. “OK, MJ, find the truffle,” he commands. MJ smells rabbit and heads in the opposite direction, all nose and puppy tail. Recalled, he focuses, sniffs out the truffle, sets his paw on the spot and sits. “Good boy.” Phoenix runs off with Dad’s iPhone to take a photo of a kookaburra and Shannon Bennett’s dad, Benny, arrives in a ute with Phoenix’s little brother, four-year-old Hendrix.

The 1930s Art Moderne house at Burnham Beeches was built by Aspro magnate Alfred Nicholas and used as a hospital, research institute and hotel until the 1990s. Since then it’s defeated different developers and is now uninhabitable though still grand and handsome, like an invitation to dream. Bennett and Garrisson’s 700-page vision document for Burnham Beeches plays like a boy’s own gourmet fantasy, except the pair’s track record suggests they’ll very likely make it all real. The mansion will include a rooftop croquet pitch and basement bowling alley. The front lawn will become an outdoor cinema and an artist will design a maze grown from hop plants. Those truffle-hunting dogs will wag in wait. The old piggery will become a bakery and light-up pig figurines will alert diners when their lunch is ready. Semi-subterranean villas and a horizon pool will punctuate the hillside. An old wheat tower will become a romantic dining turret. It goes on. “Shannon gets a vision, he goes for it, he gets to it,” says Garrisson, who has been a friend for seven years. “With a project like Burnham Beeches we will have so many hurdles and problems. If you can’t think around them, you’re sunk. He’ll push and push and make it happen.”

Gardens at Burnham Beeches already supply Vue de Monde with produce and restaurant staff are rostered to come on site to pick and pluck. Today, a bunch of waiters led by restaurant director Garrett Donovan turn up to harvest sorrel and garlic shoots. Vegetables bagged, it’s time to head via Emerald to Chestnut Hill Winery, home of the mature truffiere that has supplied the restaurant this year. But MJ fails to focus and any truffles remain hidden underground. Adam Garrisson pulls out a thermos of coffee and lays boxes of Cafe Vue cakes on the tray of a ute. The kids swarm. “What’s that orange, Dad?” says Phoenix, poking at a white chocolate confection with a sunny citrus centre. “That’s what it is: orange,” says Bennett. Phoenix chooses opera cake instead. Hendrix spies macarons. “Biscuit. Biscuit. I want a biscuit,” he says. Bennett allows one but Hendrix launches a campaign with typical pre-schooler vim. “More? Can I have one more? Biscuit! One more. Biscuit.” Dad says no. “What will Mummy say if you don’t eat your dinner?” But then he turns away to chat to winemaker Charlie Javor and Hendrix and Phoenix launch themselves. “I take my hat off to mothers,” says Bennett. “The hardest thing in the world is coming home to kids fighting.”

It’s an hour’s ride back to the city and the buzz of Saturday dinner. “I can’t stay away from the restaurant on Saturday nights,” he says. “If ever I do, I’m so distracted that Madeleine tells me to go back to work. I get separation anxiety. She reckons I need to see someone about it.” Lord knows what she thinks about the fact that Bennett watches each of his restaurants from anywhere in the world, via security cameras fed to his iPad. As well as the flagship Vue de Monde, there’s Bistro Vue in Little Collins Street, and four Cafe Vues (in the city, on St Kilda Road, at Heide Museum of Modern Art and at the airport). “The only time I switch off is on an aeroplane and Sunday nights because nothing’s open,” he says.

Shannon Bennett grew up in Westmeadows on his mum’s Irish stews and apple dumplings. From the age of eight, he was entranced by restaurants, thanks to a lawyer aunt who loved eating out and took him to fancy city institutions such as Florentino and the Hilton. When he was 13, he made a hormone-driven decision to study home economics with the girls at Penleigh, the sister school of his almer mater, Essendon Grammar. There were just three boys in the class, one of them celebrity chef Curtis Stone. While studying the finer points of sausage rolls and chocolate brownies, Bennett realised the cooking gave him a bigger thrill than the male-to-female ratio. A teenage stint at the Tullamarine McDonald’s hooked him on the buzz of service and, by the time he was 15, he was training to be a chef at the Grand Hyatt, living out of home to avoid midnight treks back to Westmeadows, winning competitions and planning career progression in the UK. In England, he worked for explosive kitchen hard-man John Burton Race at two-Michelin-star L’Ortolan and for the brilliant, brutal Marco Pierre White at his three-star restaurant at the Hyde Park Hotel. Both chefs used anger and shouting and “mentally melting people” as key motivators. “I felt a sense of satisfaction in receiving that treatment and not letting it distract me,” says Bennett. “I just cooked through it.”

A brief detour into modelling allowed him to save some money so, when he returned to Australia in 2000, he was able to open the first Vue de Monde, in Carlton. The restaurant quickly became known for outstanding modern French food in a rigorous Michelin-star mould, and for inculcating fine-dining standards in a laid-back Mod Oz world. It was almost as well known for the mercurial antics of its owner chef. “I had learnt that there was only one way to manage and that was ruthlessness,” he says. “I’d yell and scream because I thought it was the only way to get my point of view across. There was a lot of stupid management, a lot of sackings, and if that meant we only had three in the kitchen when we needed six, that’s just how it was.” Indeed, I’ve interviewed numerous chefs for this magazine who fell out of the Carlton Vue de Monde on their ear or with an earful, yet all of them speak of their Bennett days as valuable.

Critical customers got short shrift then too. Now Bennett analyses daily feedback reports and sweats over criticisms that he considers warranted. In each of three conversations for this story, he brings up a particular mistake in Vue de Monde’s bar in which a customer’s order was misplaced. The incident obviously cuts him deeply and it wouldn’t surprise me if the memory wakes him at night. On the other hand, he freely describes a tiny minority of customers as “pains in the arse” and “wankers” and tells me I’d be ashamed as a fellow human to witness their behaviour. “Some people come here with the attitude of taking your head off,” he says. “You know you haven’t designed an experience that they will like. I’m a bit more mature about it than I used to be. I analyse. I ask myself if I think other guests are feeling the same. I don’t necessarily take it to heart.”

Some grumbles about Vue de Monde don’t make him budge. One is the price tag. (A friend’s dinner recently cost her table of two $1000; she was there for an early sitting, in and out in less than two hours.) “It’s expensive because of the costs involved,” says Bennett. “The question is really, did you enjoy it? Hopefully, you enjoy it so much that it spurs you to make more income so you can do it more.” (Unseen costs include the fact that the restaurant is repainted every six months, with a timetable reminiscent of the Harbour Bridge. The wage bill, 45 per cent of outgoings, includes a tea sommelier who manages a special tea cellar which, among other treasures, holds aged pu-er leaves priced at $1000 for seven grams. The teaspoons are gold-plated and cost $250 each; $24,000 worth of cutlery has walked out of the restaurant. There was also a damage bill after a customer slammed into the Kosuth neon and kept right on walking, necessitating an urgent call to the art ambulance.)

The policy of charging a fee in the case of late cancellation or non-appearance has raised ire but Bennett is firm. “If you buy concert tickets to Stone Temple Pilots you don’t get a refund on those tickets if you don’t turn up,” he says. “We’re only asking for 24 hours notice – it’s not that hard.” There’s another delicate point: some restaurant watchers have questioned Bennett’s originality, suggesting that some Vue de Monde dishes bear resemblance to dishes at overseas restaurants. Bennett is categorical. “None of our dishes is based on any other restaurant,” he says.

Still, the shouty maestro has mellowed. Apart from anything else, he’s grown into a steely-eyed entrepreneur, perhaps a necessity when you’ve got 200 employees and hefty loans to make good. It must be stressful? “I don’t feel pressure,” he says. “The only thing I worry about is forgetting someone’s name.” What about an enormous project like Burnham Beeches? “It’s the cliche of day by day and week by week,” he says. “I think it would have been more daunting to build it in the first place. To bring back something that was grand and amazing is more exciting than daunting to me. I think it’s worth risking everything for.”

Bennett’s single-mindedness can play as hubris but those close to him think that’s a misinterpretation. “There’s no great arrogance about what he does,” says Adam Garrisson. “He just does what he does. It’s his driven nature to focus on his vision.” According to Anna Schwartz, “He approaches everything with uncompromising commitment. That leads to excellence but being ‘the best’ doesn’t come into it. I don’t see him as being competitive at all. He just has extremely high standards for himself.” A striking change in Bennett is the credit he now gives to others. The Restaurant of the Year award is “nice for the team”. Head chef Cory Campbell “has a brilliant creative mind” and “is the most gifted chef that’s come through the kitchen”. Bennett even speaks of grooming Campbell to take over Vue de Monde sometime in the future. “I never used to collaborate at all but now I enjoy it more,” he says. “Hospitality isn’t about the individual, it’s about fulfilling goals and ideas as a team. I get more pride out of that.” He expresses a collegiate affection for other Melbourne restaurateurs, wishing they met and chatted more to share ideas and lobby for industry improvements, among them better training (Bennett has developed an in-house curriculum, including a module about the world’s great restaurants) and more conducive employment laws. He thinks young chefs are paid too much for too little. “When I was an apprentice, I knew everything I was doing was an investment,” he says. “Now a lot of apprentices are being told by Mum and Dad they’re being ripped off. They don’t have the right mentality. A 38-hour week for a chef is part-time.”

Back in the Vue de Monde kitchen, he washes his hands at an eWater tap that uses salt, water and electricity to clean and sanitise without chemicals: at first the water feels thick and clammy, then as the pH level changes it feels sticky and thin. The eWater is but one of a slew of green initiatives. The kitchen uses low-energy appliances including flame-free induction cooktops. There’s natural ventilation, compost is freeze-dried for fertiliser and kangaroo-hide tables mean there are no tablecloths to launder. But Bennett isn’t quite the bleeding heart. “I got interested in the environment when I realised I had to cut costs,” he says, turning to a list of tonight’s guests. The run-sheet includes all that is known about the diners: their names, whether that’s the wife or the mistress, allergies and preferences, who’s picking up the tab and whether the bill should be brought to the table or settled discreetly out of sight. Waiters add to the information bank throughout the evening and Bennett picks over it the next day.

Rialto owner Lorenz Grollo remarks on Bennett’s facility with the finetooth comb. “He was across all our discussions: legal, lease, construction, he negotiated every detail himself.” One senses a few robust discussions along the way. “Shannon is persistent,” says Grollo. “Some of the things he pushed for were a question mark for me: the green attributes, the open kitchen concept. I didn’t think they would work. But he pulled it off. To be involved with all that innovation has been a positive and incredible experience.” The Grollos lured Bennett with rent concessions and construction assistance: they stripped out 62 tonnes of building material from the old observation deck; Bennett and his bankers fronted up for the $7.5-million fitout. Lorenz Grollo respects the chef for putting himself on the line. “It’s quite endearing for someone to go through a massive reinvention, to step out of their comfort zone, to spend millions of dollars,” he says. “It’s not something you see in many people. He’s taken a massive risk for his business, his profile and his credibility, but he’s made it work.”

Bennett carries a coffee percolator to a table to brew soup for guests and, later, pours liquid nitrogen into a bowl to freeze-dry herbs for a laugh-out-loud palate cleanser. “It’s about fun and a sense of occasion,” he says. “It’s a show.” Still, he sees himself relying less on bells and whistles as time passes. “I used to think presentation was absolutely everything. Now I think we have that under control.” One thing is certain: the Vue will keep changing. “The satisfaction bar always moves,” he says. “I don’t want anything I do to ever sit still.”

Click the image above to read the article as it appeared in the age (melbourne) magazine

Leave A Comment