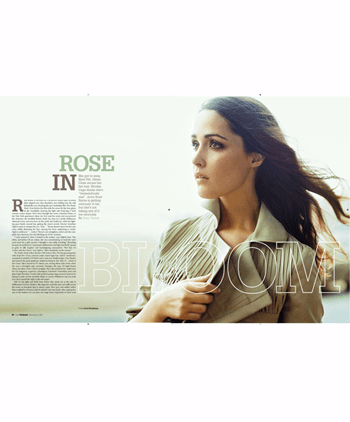

She got to snog Brad Pitt. Glenn Close envies her hair. Nicolas Cage thinks she’s “tremendously real”. Actor Rose Byrne is getting seriously A-list, but she’s not taking any of it too seriously.

Rose Byrne is sitting on a rumpled single bed, flapper dress slipped over slim shoulders, eyes drilling into the wall behind the crew shooting the new Australian film The Tender Hook. Even before the film rolls for scene 84, her face glows in the viewfinder, drawing the light and bouncing it back warmer, richer, deeper. She’s been through this scene a hundred times, in her New York apartment where she first read the script and encountered her character, the troubled femme fatale Iris, then in a sterile Melbourne rehearsal room, and now here, in this seedy attic bedroom, while the lighting guys bustle around her, getting the mood sorted. Director Jonathan Ogilvie starts to whisper his cue. “And …” Byrne doesn’t move but her eyes cross wildly, distorting her face, turning her from captivating to wacky. Ogilvie continues: “… action.” Byrne’s eyes straighten, soften and she catapults into character, into the blinding eye of the moment.

“I only noticed it when I looked at the rushes,” says Ogilvie later, “but often, just before I’d say action, she was concentrating so hard she went cross-eyed for a split second. I thought it was really revealing.” Revealing because on set Byrne is “casual and collaborative and light and fluffy”, prone to gales of silly laughter and backslapping camaraderie. “But then it’s Â’action’ and she’s there,” says Ogilvie. “She’s absolutely on the money.”

The Tender Hook is Rose Byrne’s 19th feature film. She has ground groins with Brad Pitt (Troy), tottered under metre-high hair (Marie Antoinette), screamed at zombies (28 Weeks Later), won over Heath Ledger (Two Hands) and entered the geek pantheon simply by being in Star Wars II – Attack of the Clones. She’s starred in TV shows, too: among them Echo Point, when she was a schoolgirl, and, currently, Damages, the pacy US legal drama where she plays Glenn Close’s protégée. She’s also posed in her underwear for GQ magazine, acquired a photogenic boyfriend (Australian actor and playwright Brendan Cowell) and sparked gossip-mag anorexia hysteria by daring to poke out her shoulder blade at a party. Whichever way you look at it, she’s earned the right to the red carpet.

Still, it’s the light and fluffy Rose Byrne who meets me at the cafe in Melbourne’s Fitzroy Gardens. She snaps her umbrella shut and walks across the room on beanpole legs in skinny jeans. She’s spry and smiley rather than swathed in charisma and she doesn’t turn any heads. After sipping her way to the bottom of a soy latte, she slugs from a big bottle of water and, every so often, runs her fingers through her thick hair. “My brother calls my hair The Brown Curtain,” she giggles. She laughs frequently, as if it’s a great relief, displaying a snaggle tooth that never seems to appear on screen. After each guffaw, she recovers with a gasping intake of breath. She talks about herself for two hours with good grace but little relish. (“You really want to talk about my childhood? No, that’s okay …”) Frequently, she veers off-topic, asking me questions or rabbiting about her favourite TV shows (Big Love, Curb Your Enthusiasm). She comes across as pleasant and smart and unaffected and not particularly steely or intense.

Three weeks earlier, I had watched Byrne on the set of Knowing, a thriller shot in Melbourne this past winter and starring Nicolas Cage. Byrne co-stars as Diana, a single mother in the thrall of her own mother’s spooky predictions. On day 29 of the 55-day shoot, Byrne was in a massive DockÂlands shed, filming a scene that required her to take four steps towards the camera, then put her hand to her mouth in shock. She had already done eight or nine takes.

This time, director Alex Proyas called, “Cut. Great, Rose.” Suddenly, the crew bustled about as if Sleeping Beauty had just got her wake-up kiss. Blokes in beanies wrestled fake trees into position, a gofer ground coffee, a publicist passed headphones to a German journalist. But, even though the camera had stopped, Byrne kept her freaked-out face on, eyes darting side to side as if she had really seen something worth running from.

Finally, she shook herself out of character, flicking off her own electricity. I didn’t see any crazy crossed eyes, but it looked as if she was in very deep. During the lunch break, Byrne flipped to fluffy mode for a press conference, patting Nicolas Cage on the shoulder when he stumbled over a word. She sat back when Cage gave his co-star’s intensity the stamp of approval. “Rose is tremendously real in the scenes,” he drawled. “She has an ability to make us feel as though it’s actually happening.” So, how does she do it? Cage shook his head, swallowing the words as he spoke them. “That’s her mystery.”

Rose Byrne, 29, has been acting since she was a toddler. older brother George recalls her playing the sun in a family play, “perched on a rafter in the garage, swishing orange and red material with her stubby little arms”. Rose was the youngest of four children in the Byrne family’s two-storey timber house in Sydney’s Balmain. Her father, Robin, was a maths boffin who analysed retail statistics; her mother, Jane, juggled the kids and a job at a Redfern primary school. (Robin and Jane have now moved to a bush block in Tasmania, where they’re fostering their youngest daughter’s schnauzer, Des.) According to Rose, she was “definitely a show pony as a little girl, always trying to make them laugh, it was a bit of a performance the whole time”. George Byrne reckons his baby sister didn’t have to try hard to be noticed. “She’s always been an expressive, passionate, intelligent, funny little kook whose cuteness made her hard to ignore,” he says.

The family was firmly anchored in the neighbourhood. “It was a magical, wonderful place,” says Byrne, describing a milieu infused with a golden feeling of possibility. “We grew up with a lot of artists. The community encouraged that,” she says. “Our parents had a certain amount of ease and relaxation.” Her friend, singer Holly Throsby, lived one street away. “We were in the midst of this kind of bohemian hangover of the early 1980s,” says Throsby, noting that she and Byrne, and musicians Alex Lloyd and Josh Pyke, emerged from the local primary school at the same time. “We were all very well-loved but we were also given a great amount of freedom. We would play in the streets on our bikes and sell our paintings for 10 cents at our street stalls while our parents would all be hanging out, drinking gin and tonics and talking about the Labor Party.”

When she was eight, Byrne started taking weekly classes at the Australian Theatre for Young People, a well-established thespian proving ground (alumni include Nicole Kidman, Baz Luhrmann and Toni Collette). “I loved it, I really took to it,” says Byrne, whose passion for performance Âdeveloped in parallel with a love of Kylie Minogue. “I was her primo market, I went to all of her concerts,” she says.

Byrne started secondary school at Hunters Hill High School, across the harbour from Balmain, and got her first acting job at 13, playing a sassy UFO-watching teen in the film Dallas Doll. “That’s when I thought, ‘Shit, I could do this for my career,’  ” she says. Even as she blossomed, she stayed grounded, says Throsby. “There were girls in high school who were affected and wore make-up and knew they were pretty, but Rose was never like that. She was just hanging out in old jeans and overalls.” The pair would sit up the back of the class “and talk about stuff that was fascinating at the time: River Phoenix, cold sores, Baileys Irish Cream.”

Sydney actress Nadia Townsend became friends with Byrne in their year 9 science class. “I thought she was pretty cool,” says Townsend. “I was a homey in baggy pants and Nikes. She was a hippie, in crocheted dresses and long hair. I was into hip-hop and she was into Lenny Kravitz. I wanted to be like her.” The two cemented their friendship by wagging school sport every Tuesday. “We’d go into the city and practise Academy Award acceptance speeches on the St Mary’s Cathedral steps.”

Townsend also spent time with the Byrne family in Balmain. Entering their home was “like walking into a lovely warm cup of tea”, she says. “It was a very supportive household, one of those houses you walk into and think, ‘Ah, I want to stay here.’ ” The way Townsend tells it, classical music blared from the radio, Jane Byrne was “always caning through novels” and Robin Byrne, a “super-smart” eccentric with “crazy, white, wiry hair”, constantly cooked for a crowd, unless he had embarked on an hours-long mission to buy a particular loaf of bread. “They used to have massive family dinners, the kids would bring friends. It was one of those houses that everyone Âalways came to.”

Byrne started popping up on TV shows, including a regular role in the soapie Echo Point when she was 15, and a dollop of instant fame came with it. “There was make-up, lots of attention, I was getting hassled a bit at school,” she says. Then the ratings dived and the show was shoved to a late-night timeslot. “All that stuff completely vanished. It was a good crash course in fame.” The Hunters Hill High crowd was “quite wild”, according to Townsend, and she and Byrne partied with the best of them. Then, at the end of year 10, the two friends got serious about their studies and acting aspirations and shifted to Bradfield Senior College in Crows Nest, which offered a drama course. “We went with a whole studious attitude for year 11 and 12,” says Townsend. “But everyone else who went there realised they were gay and shaved their heads and got piercings and smoked bongs in the dunnies. So, we basically just had each other. It was intense.”

Byrne progressed as an actor. “Drama was just something that we loved to do but she was always particularly watchable,” says Townsend. “She had a natural ability to handle it, a natural love of being on stage.” In English class, Townsend noticed how switched on Byrne was when it came to analysing texts. “Even Brendan [Cowell] has mentioned that to me,” she says. “He said when she reads his plays she picks up things that no one else has.”

In 1997, Byrne got a part as a drug-addled street kid on the ABC-TV drama Wildside, which pioneered an energetic, gritty realism. The dramaturge on set was Nicholas Lathouris, “a really great coach”, according to Byrne. “We were testing out a whole new approach to acting, working with improvisation, directing on the fly,” says Lathouris, recalling a car chase where Byrne hung out the window shouting obscenities and another scene where Byrne’s character harassed a receptionist. “Rose was full of courage and daring. She was out there exploring the medium, right on the edge.” Fast-paced improvisation meant the line between fiction and reality got blurred and Wildside actors had to draw on personal resources, not just acting skills. “In other words, you’re only as good at acting as you are at living,” says Lathouris. “Rose just went for it, 100 per cent. It was a bit scary, actually. Rose was a window into truth.”

The following year she was in Two Hands, the film that really launched her career, playing a savvy but green country girl who steers Heath Ledger’s character towards salvation. “I was myself, that’s why I got the role,” she says. “I look back at it now and think I look so young and terrified.” Director Gregor Jordan was attracted to Byrne’s spirit. “She had this real liveliness, she made the character come to life,” he said at the time. “And she’s very, very beautiful. She looks amazing on screen.”

Byrne and Jordan fell into a relationship during the shoot and stayed together for three years. “It was a really pivotal time in my life, personally and professionally,” says Byrne. At the time, she was studying arts at Sydney University, majoring in English literature (“my great love”), just in case the acting didn’t work out. “It’s a shame I didn’t finish my degree,” she says, not quite convincingly.

In 2000, Byrne played a disturbed blind girl in Clara Law’s film The Goddess of 1967. “That was by far the biggest role I’ve had to do. It was huge,” says Byrne. Learning to act blind was the first challenge. Over two months, Byrne watched videos of blind people, visited a blind institute and stayed with a blind person. “I told her I wanted her to come to the set blind, not trying to be blind,” says Law. “It was a long but fruitful process.” Law had initially been attracted to Byrne’s look – “a combination of fragile and strong: I think that’s her essence” – but as the shoot went on, the director became more and more impressed by Byrne’s courage, especially while filming a raw and emotional sex scene. “That day was the hardest day in her life,” says Law. “It was her first time playing that kind of scene and she felt totally exposed. But even so she played it in a very devoted way, head-on, even though she was very vulnerable.” Playing angry also posed difficulties. “She is a mild-tempered, gentle person and at some point she had to play a totally angry, very strong person.” Byrne wasn’t able to summon up the requisite rage, so Law put down the script and workshopped anger for a day. “We had to break through a block. We improvised many situations until she reached a point where she became really, really angry. Then I told her that was what I wanted to capture.” Once she’d been there, Byrne had no trouble getting back. “When we did the scene, she totally convinced me that she was full of that anger. She was remarkable,” says Law. Byrne won the Best Actress award at the 2000 Venice Film Festival for her performance.

She got busier, winning roles in films such as Star Wars II and British period piece I Capture the Castle. Her Balmain buddy Alex Lloyd was particularly impressed with the latter, and not just because Byrne nailed the English accent. “This was the first time I couldn’t see Rose any more,” he says. “I didn’t pick up any of her personal traits. I didn’t see her as a friend, just as a character on the screen.” In 2002, she starred in the Australian comedy The Rage in Placid Lake. It was her comedic debut, but director Tony McNamara reckons “she’s a natural comic, Lucille Ball funny”, at least partly because she’s “very idiosyncratic, very aware of bullshit, with a good sense of the absurd”. He also notes that his star ate lots and lots of lollies. “She would have sugar rushes in the middle of shooting and start biting crew members in a kind of mad, great way. She’s not precious at all.”

In 2003, Byrne endured five months on location in Mexico and Malta to shoot epic battlethon Troy. “I found that really hard,” she says, painting a picture of a shy Aussie chick reading Naomi Klein’s anti-Âglobalisation book No Logo in a caravan while shiny-muscled stars hogged camera time. “I wouldn’t work for three weeks, then I’d work for a day. It was awful. I went nuts. I’m not really big on lying around a pool, so I’d walk into town, walk back, read. It was bollocks.” Working with Brad Pitt was some kind of pay-off. “BP was great,” she says. “He was very generous, a really nice guy. He was very collaborative.” And the love scenes? “Well, another day at the office,” laughs Byrne. “What can I say?”

After Troy wrapped, she didn’t work for a year – “part-recovery, part-unemployment” – then got back on the bike with Wicker Park and, in 2005, Marie Antoinette, where she played a provocative party-girl leading the queen off the straight and narrow. Byrne read plenty of French history before she rolled up at Versailles, but the swotting was nothing on the three hours a day spent piling up her hair and donning complicated 18th-century costumes. “It was like time-travelling,” she says. “It makes you walk differently. Your posture is different. It informs your performance.”

Danny Boyle’s sci-fi film Sunshine required preparation of another sort. “We had a three-week boot camp, experiencing zero Gs in a small aircraft and meeting quantum physicists and futurists, insanely intelligent people who would come to talk to us, a bunch of stupid actors. They trained us up good.” Boyle’s next film, 28 Weeks Later, allowed Byrne to fulfil a secret teenage ambition to act in a horror film. This time the major challenge was getting out of bed: much of the shooting was in the wee hours when the film crew could have the run of London. “I’d always be getting up at 3am for these two-minute slots where they’d clear the streets. We had Shaftesbury Avenue from 6 to 6.02 on a Sunday morning. I was tired the whole time. I fell asleep in the weirdest places, like on a chair in the middle of the street.”

Byrne lived for a couple of years in London and materialised on the red carpet here and there, but she stayed tight with her mates. “A package always arrives in the post for your birthday, or if she hears your dog’s died, she’ll call,” says Townsend. She’s no big-noter, says Holly Throsby. “She’ll have a pivotal role in a big Hollywood movie but she’ll say, ‘Nah, I’m hardly in it.’ She is hilariously self-deprecating.” She has her girly moments, too. Back in Australia this winter, Byrne and her Tender Hook co-star Pia Miranda stayed in touch while indulging their shopaholic tendencies. “We were doing a lot of texting from the change rooms, lamenting that we were both on a first-name basis with the girls at our local Sportsgirl,” says Miranda.

Keeping close to family is part of the Rose Byrne modus and, when the family gathers, the youngest daughter reprises her role as show pony. “She’ll be sitting there completely mute for an hour, then she suddenly launches,” says brother George. “Sometimes it’s a loose, flowing, abstract delirium, other times it’s more refined and coherent, always off the cuff and totally ridiculous.” When she’s away from Australia, Byrne is inclined to fly in friends – and her boyfriend – to keep her company, rather than be stuck in another Troy-style nightmare.

After an hour and a half in the cafe, the rain clears and Byrne suggests a wander around the gardens. A schoolgirl gets in her way, apologises and Byrne almost shouts her forgiveness: “Hey, that’s okay!” As we walk, she talks about her profile, insisting that she still misses out on roles to bigger names and rarely needs to dodge paparazzi. “I fly under the radar, I’m virtually anonymous.” She’s happy with her trajectory though. “I’m really proud of my career. I’ve worked really consistently. Now I’m nearly 30 and I’m getting meatier roles, not just the pretty girlfriend roles. I’m not an ingénue any more and it’s kind of a relief. And my dance card is full.”

At the moment, she’s living in New York, working at a cracking pace on the second series of Damages. Glenn Close, who won a Golden Globe for Best Actress for her part in the show, describes Byrne as “a great foil, a workhorse, one of the pillars of the whole project” and a “really masterful actor who dug deep” to develop her character. She enjoyed Byrne between takes as well. “Rosie has a breeziness about her. She comes on set to work but she’s ready to laugh. It’s an important ingredient when you’re working 14-hour days.” Close also admits to a little jealousy. “She’s unbelievably beautiful. I wish I had her hair. And her nose!”

Dramaturge nicholas lathouris says film-industry people are always sitting around trying to decode the mystery, wondering what makes one actor great and another actor, well, unemployed. He’s pretty sure it’s not the hair or the nose or even whether they go cross-eyed before an intense scene. “It’s something to do with feeling a connection to everybody, knowing that there’s a common humanity in you that you want to give back to the audience. A lot of actors want to be seen for who they are, but the great ones – like Rose – search for the essence of all of Âhumanity, that feeling of belonging, then they share it. It’s totally profound. It’s way beyond ego. And whatever it is, Rose has got it.”

Leave A Comment