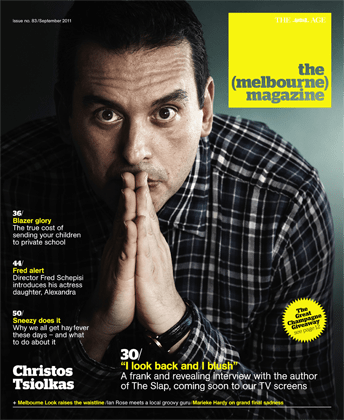

The Slap “one of the most talked-about novels of recent years” is now a TV series. Here, its author, Christos Tsiolkas speaks with Dani Valent about the time he was slapped himself, his stint in a fundamentalist Christian group, and his “own dark soul”.

Click here or on the image above to read the article as it appeared in the (melbourne) magazine

I ring a doorbell in Brunswick and before the echo ebbs, there’s a tumbling sound, boots rushing down stairs, then a steel door swings opens and a face pops out, all bright, dark eyes: Christos Tsiolkas, eager as a puppy, pumps my hand, ushers me upstairs and wonders if I’d like coffee. Two hours later, he stops talking. It’s not that he hasn’t drawn breath, more that he hasn’t held back. He’s voluble, thoughtful, keen. He asks me if his answers make sense (they do) and he apologises plenty for straying off topic (it’s fine). He uses my name a lot and, when I leave, he gives me his phone number on a bright pink Post-It in case I need more.

Since its release in 2008, Tsiolkas’ novel The Slap “which centres on an adult smacking a naughty child who isn’t his own” has won swags of prizes and sold more than 600,000 copies around the world, including 200,000 in Australia. It’s now been made into an eight-part television drama series, soon to screen on ABC1. And it’s probably been discussed at just about every book group and barbecue in Australia and certainly at every playgroup and kindergarten, where other parents’ parenting is always on the agenda. Even so, Tsiolkas, 45, doesn’t think it’s a great book. “I don’t think I’ve written a great book yet,” says the author of four novels, half-a-dozen plays and two screenplays. He chooses his words carefully, his art-wanker radar on high alert.

“It’s so hard to say,” he says hesitantly, hauling the words up like boulders. “What I want to be is a great writer. Of course I do.” He sighs. “At the risk of sounding like a nostalgic old codger, I used to use the words “masterpiece” and “great” all the time. Every third film I saw was a masterpiece. Every third book was fantastic. But with experience comes the realisation that greatness is a very rare thing. I would love to write a great book. Of course I would. But the fear that will never go away is that I’ll never do it.”

Humility? Trepidation? Isn’t this the fearless, frabjous bad boy of Oz Lit, whose books use depictions of violence, drugs, madness, masturbation and other unglamorous sexual expression to push deeply flawed characters along troubling, anguished and very dark plot lines?

We’re speaking at his Brunswick studio, a sparse, bright factory space shared with a film production company and another local writer, Peggy Frew. His writing patch is small and open to the room: there’s a small desk, a laptop, dictionary, thesaurus and notebooks. The studio is a new investment, possible only because the success of The Slap allowed Tsiolkas to ditch the earn-a-crust work he’s juggled alongside writing ever since he devoted himself to the craft in his mid-20s. Along the way he’s worked as a film librarian, cinema curator and most recently as a veterinary nurse. “Work has been a reminder that there is a world outside writing,” he says. “That richness has been a bit of a lifesaver, a grounding thing.”

The perspective was never sharper than one day in 2009 when Tsiolkas told his vet clinic colleagues about winning the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize. “They were thrilled for me, they hugged me, we rejoiced,” says Tsiolkas. “Then my boss told me the kennels needed to be cleaned.”

With literary success, and no kennels to clean any more, Tsiolkas realised he needed to create his own structure. “As soon as that other work was gone, I was just wasting my time, putting on four loads of washing, roaming the internet for obscure pop songs from the early ’80s “the usual,” he says. Now he has a selfimposed schedule and even a commute. Tsiolkas relishes the hour-long rumination and perambulation from his home in Preston, where he lives with Wayne van der Stelt, his partner of 26 years, along Merri Creek and Sydney Road to the writer’s desk, where his only job is to create. “I realise how lucky I am,” he says. “But there is a certain fear and anxiety that goes along with success.” It starts to makes sense that Barracuda, the novel Tsiolkas is working on now, is all about failure.

The novel is about a swimmer who dreams of competing in the Olympics but never makes it. “He’s a working-class boy with phenomenal talents who gets a scholarship to an elite school,” says Tsiolkas. “I’m fascinated by failure and success and we’re Aussies, so sport is a huge metaphor for that.” But sport is much simpler than life or art. “What I like about sport is that you have that cleanliness of being the first one across the finish line, the one who scores the most,” he says. “There is something concrete that can be marked in time and space: you really are the best athlete, the best swimmer.”

Tsiolkas has real-world experience of failure. His first book, Loaded (1995), a gripping, Greek, gay-focused example of grunge-lit, was made into the film Head On. But his second book, The Jesus Man (1999), an ambitious unravelling of racism, economic rationalism, sexuality, pornography and insanity, was slammed by many reviewers. “I will always feel a tenderness towards The Jesus Man,” says Tsiolkas. “It made me realise I wasn’t a wunderkind, that I could do things that would fail.” He considered giving up writing. “There was a point where I didn’t want to do it anymore. It hurts too much. But I’m really glad I didn’t make that choice because I think writing is the thing I need to do.”

He fronted up seven years later with Dead Europe (2005), another difficult read, a kind of exorcising of Europe that looked at anti-Semitism from the inside. That book won The Age Book of the Year fiction prize and has recently been greenlit for film production. “I’m most proud of Dead Europe because I was testing myself as a writer with that book, trying to find new ways to not be safe,” Tsiolkas says. There was a cost, though. “Dead Europe did tear me apart. I went into all these dark places that were terrible to be in.” In comparison, The Slap was easy: it tumbled from a world Tsiolkas knows and he found it easy to be ruthless about it. “With The Slap, it was just the pleasure of creating characters and stories and writing about Australian life. It was an effortless ride. There’s an element of feeling a little ashamed of that.”

Perhaps it’s more that he doesn’t feel entitled, having grown up with immigrant Greek parents who worked in factories and as cleaners, didn’t read English

and found the middle-class milieu, and especially its artistic cliques, “threatening”. “They’re not from this world,” he says. “I’ve been educated, I went to uni, I know how to navigate it.” Even so, Tsiolkas carries a legacy in the form of an imaginary Fake Spotter that he still fears will shake its head sternly, tell him he’s been caught out and haul him away.

He’s able to enjoy his success though. He can take the load off his partner Wayne as chief breadwinner and he can encourage his parents, George and

Georgina, to stop worrying. “For my family, it’s been such a relief and a joy to know that I can support myself with writing. Finally, they can be proud.” Pride blossoms in strange places. “At the deli where my mum shops, they would only ever ask about my brother John, a lawyer, and his daughters. There would

be this silence about me, the strange gay one who wrote profane books.” But then The Slap made it into the Greek newspapers. “Suddenly, they started asking

her, “˜And how’s Christos? Send him our love.'” Tsiolkas spills with shiny-eyed laughter, as he often does when there’s an opportunity to relish lovable, fallible humanity. But there’s a serious side to managing success. “I keep telling my parents, “˜This wasn’t planned, we can’t count on it, I will continue to write the kind of literature that I want to write, so just let’s enjoy this.'”

Tsiolkas was born in 1965 and, until he was 10, the family lived in Richmond, in an almost exclusively Greek enclave. “When I started primary school, I really did think Greek was the language of Australia because that’s what I heard around me,” he says. “I was put in a class with newly arrived migrant kids.” He was a motivated student. “I remember wanting to conquer reading,” he says, and he quickly became an avaricious consumer of books, supported by his father. “My dad would buy me two books from the newsagent with every pay cheque, everything from Harold Robbins to Henry Miller to Charles Dickens to Carson McCullers,” he says. That unrestricted bowerbird approach applied to screen culture too. “My parents would watch TV programs with us, and take us to the movies because they would want us to translate for them. I’m so grateful for that uncensored upbringing.” It was a social existence too. “As a young child, I possessed my street along with all the other kids. We all walked to the same school, our parents worked in the same factories, we were in and out of each other’s houses all the time.” He became a Richmond Football Club supporter without deciding to. “It was like growing up Greek Orthodox. I didn’t know there was a choice.”

Most Saturday nights the Tsiolkas family would watch Greek movies, either at the National in Richmond or the Westgarth in Northcote. “And when we got bored, the kids would play up and down the stairs, dozens of us. I’m hesitant about nostalgia but it feels like a very charmed and free existence in retrospect.”

Tsiolkas started to become aware that he was gay when he was still in primary school. “I didn’t know what it meant, exactly, but I remember vivid desires as early as 10 years old,” he says. “I knew I was going to have to deal with it and there was a long process of preparing myself for the battles that I knew would come.” When Tsiolkas was in year 8, the family moved to “very white, very Anglo” Box Hill North, a move that coincided with adolescence and intensifying confusion about his sexuality.

“I felt friendless and lost,” he says, and he became caught up with a fundamentalist Christian group. “It was a way of trying to avoid the reality of what I had to be,” he says. “I became convinced I was evil, that my very essence was hellish. It scarred me for a long time.”Cinema was crucial in exposing him to other ways of seeing and being. “It saved me,” he says.

But the education and art that helped Tsiolkas come to a personal understanding also drove a wedge between him and his parents. “They were classic migrants ““ they wanted me to be a lawyer, doctor, accountant or teacher. I knew from early on that I wanted to write.” Tsiolkas aimed himself at an Arts degree at the University of Melbourne, immersed himself in political thought, student politics, publishing (he was editor of the student newspaper Farrago in 1988), drugs, and the early days of his relationship with Wayne.

He styled himself as an Artist. “I thought I was King Shit,” he says. “I was immersed in the myth that you had to be suffering and in pain and incredibly arrogant and cruel to do justice to art with a capital A.”One day he visited the family home in Box Hill North and found his father tending his vegetables. “Dad loves the garden,” he says. “He grew up with 11 siblings in a two-room shack and that day he was telling me, or trying to, just how important it was for him to have this land. I was there, arrogantly dismissing it as nonsense, trying to explain Marxism and notions of property. I look back and I blush. I was too arrogant to understand the courage that it took for him to create something in Australia.”

Tsiolkas doesn’t only cringe about the way he treated his parents. “I’ve done despicable things, things I’m ashamed of,” he says. “I have betrayed Wayne’s love and we were apart for a period of time.” Tsiolkas credits shame with pushing him to maturity. “I can no longer access that self-righteousness I had

as a young man. I also understand how difficult relationships are and how complicated love is and how painful it can be,” he says. The mercilessness and

selfishness has been sequestered in his writing. “Fiction allows me to explore extremes that, if I was to explore in my relationships, would result in me being single and rather friendless.”

Tony Ayres, producer and director of The Slap drama series and long-time friend, notes a disjuncture between Tsiolkas’ angry writing and his genial personality. “His writing is so dark and muscular and provocative but he’s so warm and generous,” says Ayres. “He’s open, he has an appetite for fun and an

enthusiasm for life.” Ayres regards that paradox as essentially human. “We’re all contradictory and, as a writer, Christos has a facility to manifest those

contradictions and to look at the fractures and contradictions within any position,” he says. “That’s what makes his writing so interesting. The questions

he raises are always fantastic.” Ayres and Tsiolkas spent three weeks workshopping The Slap with the show’s five writers. “I was nervous, seeing all these

copies of my book, annotated and covered in little yellow stickers,” says Tsiolkas. “And I think the writers were worried that I was going to be really precious. Then all that evaporated.” Tsiolkas gave license and “we ripped the book apart”. The collaboration was energising. “It was a wonderful experience to work with a roomful of people.”

Tsiolkas hopes to experience more of that vigorous criticism in his own writing circle, which meets fortnightly. “I want people to be even tougher with me,”

he says. Tsiolkas spent time on set too and found it fun, exciting and occasionally heart-stopping. “I was there when Sophie Lowe and Blake Davis, who play

the teenagers Richie and Connie, were filming an emotionally raw scene when she talks about being raped. I watched these fine young actors immerse

themselves in these characters and go to that place. I just wrote it but they give it flesh. That experience was incredibly moving.”

Tsiolkas speaks about two instances in his own upbringing in which he was clipped across the head and, lo and behold, the sky didn’t fall in. The first was when he was a young child: if Tsiolkas and his brother were being naughty, resisting bedtime perhaps, their mother would turn off the light, whack them, flick the light back on and proclaim that the punishment was at the hand of the Virgin Mary. “The Virgin Mary is ever vigilant,” he laughs.

The second slap has a reprisal in The Slap. “When I decided to study at Melbourne Uni, I didn’t even know where it was, that’s how green I was,” he says.

“A very close friend of my father’s, a man who came over in the same ship as him, drove me to uni, pointed to one of the yellow brick buildings and

told me that he was one of the men who built it. Then he slapped me lightly on the back of my head and said, “Don’t ever forget that’. And I don’t think I ever will.”

That kind of conscious consideration of different lives, different perspectives is where Christos Tsiolkas, savage and angry writer, and Christos Tsiolkas, warm and friendly person, seem to merge. He’s compelled to investigate the way life is rewarding for some, impossible for others and how the pathways between might be navigated. He’s worried about Melbourne and Australia, about lazy opinion and self-satisfied apathy, and more particularly, a lack of infrastructure spending and the treatment of refugees.

“That’s where The Slap comes from. Here is this city, this country that has grown so fat, so bloated, so wealthy and I know. I’m sure of it, we’ll turn around in the future and say, ‘We pissed it up against a wall, we created nothing. What have we done about transport? About public education?”

He is annoyed, generally, by how much Australians whinge. “Greece has 43 per cent youth unemployment,” he says. “I can’t quite understand why we don’t grasp

how fortunate we are.” Above all, he’s worried about good, evil and the struggle between them. “I wonder about my own dark soul,” he says. “If I see a film about the French resistance I might dream I would have become a resistance hero but I can also see how I would have become a collaborator. “Those are the sorts of questions I want to consider: how do we become that which we fear and detest, how do we acquiesce? I put that in my writing but I also see it as a constant challenge in my life.” Put simply, it’s not simple to be human. “All good art knows that,” he says. “The struggle to be good is hourly, daily, that’s what I’m so conscious of, in my writing and also in my life.”

Leave A Comment